Why Dividends Suck

Contents

Browse through any investment community discussion on dividends, and you’ll encounter myriad misconceptions about dividends. Here are some of the comments displaying the range of misconceptions related to dividend investing.

“Dividends are for income generation, not for growth.”

“Investing in dividend stocks is the best way to plan for retirement.”

“Dividend stocks are for protecting the wealth you make from growth stocks.”

“Dividends protect shareholder value because otherwise companies would be engaging in buybacks at prices too high to justify.”

“Dividends are only worth it when you already have hundreds of thousands of dollars in capital.”

You might actually find yourself agreeing with some of these comments. Certainly, many of them seem rational on the surface, but as you will later see, none of these ideas are actually correct.

But perhaps the most egregious misconception among investors is that dividends are essentially free money – that with a dividend stock, you get to hold the stock and receive income while doing so. This could not be further from the truth. A common saying in economics is “there is no free lunch,” and this is no less true for dividends.

Dividends Are an Obstacle to Wealth

No investment offering an obvious benefit comes without a detriment. While dividends attract both new and seasoned investors looking to generate income while holding stock, the truth is that dividends are an illusion. They are not free money, and the perceived flaws, such as low return, are not the actual flaws that come with a dividend-focused portfolio. In fact, once you go down the dividend rabbit-hole, you will find the very action of seeking dividend stocks will lead you down a road with many more obstacles to wealth than short-cuts.

Consider two stocks: stock D, which offers a dividend, and stock N, which offers no dividend. Both stocks trade at equal value: $100 per share. Stock D, however, pays a quarterly dividend of $1, which is a pretty standard value for a dividend, equating to 4% annual yield. All things being equal, which stock would you prefer?

The natural response is to gravitate toward Stock D, as buying the stock not only gives you partial ownership of the company but also the dividend payment. Someone playing devil’s advocate might state that Stock D is likely inferior, as dividend stocks are not growth stocks and thus have less upside. Not only is this not true but it adds assumptions to the hypothetical problem.

The hypothetical problem states nothing about the stocks’ profiles – just that one offers a dividend while the other does not. All things being equal, it would seem that Stock D is the better choice. But the truth is Stock D is – at best – equal to Stock N.

The Birthday Problem

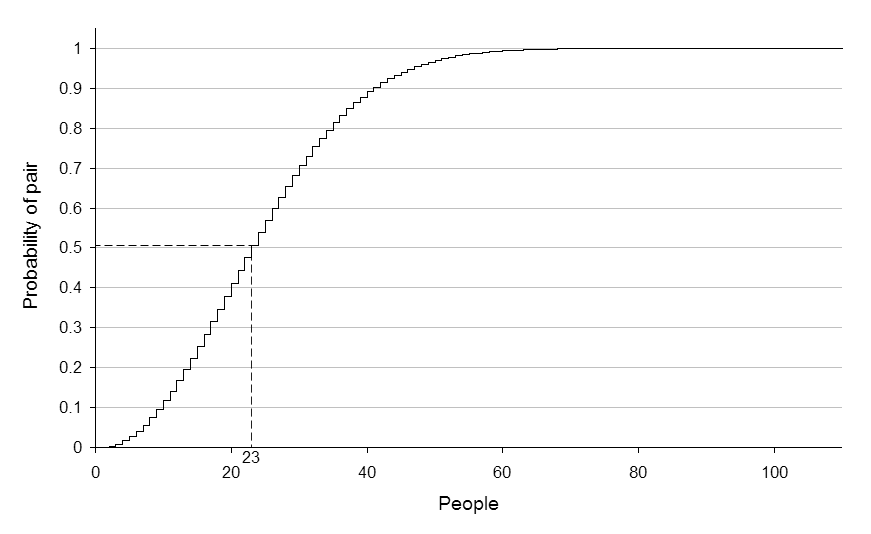

This result seems counterintuitive, but like many things in life, once a problem involves some mathematics, our intuition falls apart. Consider the birthday problem – a problem often introduced in undergraduate probability courses. The problem is generally stated as a question: “How many people would you have to put in a room to have a 50% chance of two of them sharing a birthday?”

Ignoring leap years, the probability that two people share a birthday is one over 365. A common first guess to the birthday problem is that we would need around 180 people in the room to generate a 50% probability of two of them sharing a birthday. The actual answer to this problem, though, is only 23 people.

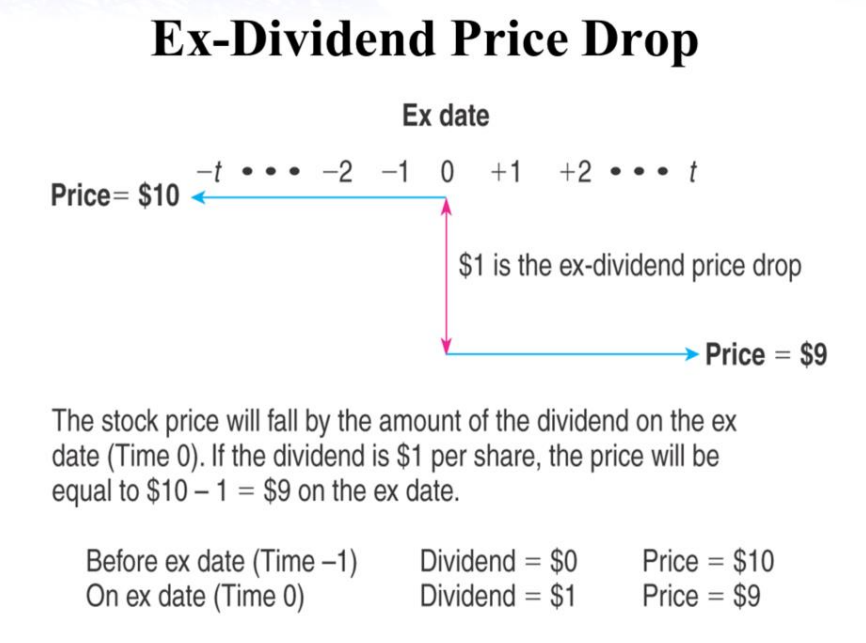

Returning to the comparison of Stock D and Stock N, two otherwise identical stocks, Stock D is counter-intuitively equal to Stock N, ignoring taxes. To see why this is so, you only need to look at the behavior of dividend stocks on ex-dividend days. For nearly every dividend stock, the stock price drops by roughly the dividend amount on the ex-dividend day.

Thus, for stock D, the $1 payout in the form of dividends is matched with a reduction in the stock price by $1. The net result is a stock priced at $99 after the ex-dividend date and a dividend of $1 collected on the payout date. Ignoring taxes, the sum value is still $100, equal to the value of Stock N, which did not pay a dividend nor fall on the ex-dividend date.

Ex-Dividend Arbitrage?

If the ex-dividend price drop is a novel concept to you, you likely will have two natural follow-up questions. The first is a rather straightforward thought but is a sign of a good investor:

“Is there a profit opportunity in this?”

In fact, there is. It is called dividend arbitrage but is quite difficult to pull off in the actual market.

The second question is, “How is Stock D’s dividend any different from selling 1% of Stock N?”

The answer to that second question is, “It’s not.” Or more correctly, “It’s worse.” That is, an X% dividend is worse than selling X% of your shares.

The reason is taxes. Selling your stocks’ shares is taxed at capital gains tax when sold at a profit. Dividends are taxed as income and thus at a higher rate.

In addition, when a stock is sold at a loss, your share liquidation entitles you to a tax loss carryforward. A dividend, however, is always counted as profit and taxed as income. This is true even if your initial investment in the dividend stock is currently at a significant loss.

Ignoring taxes, however, selling 5% of your shares in a non-dividend stock per year is mathematically equivalent to holding a dividend stock with a 5% yield. That is, any stock can act as a dividend stock. The myth of dividend stocks being income generation is just that: A myth – any stock can act as income generation via the sale of a certain percentage of shares.

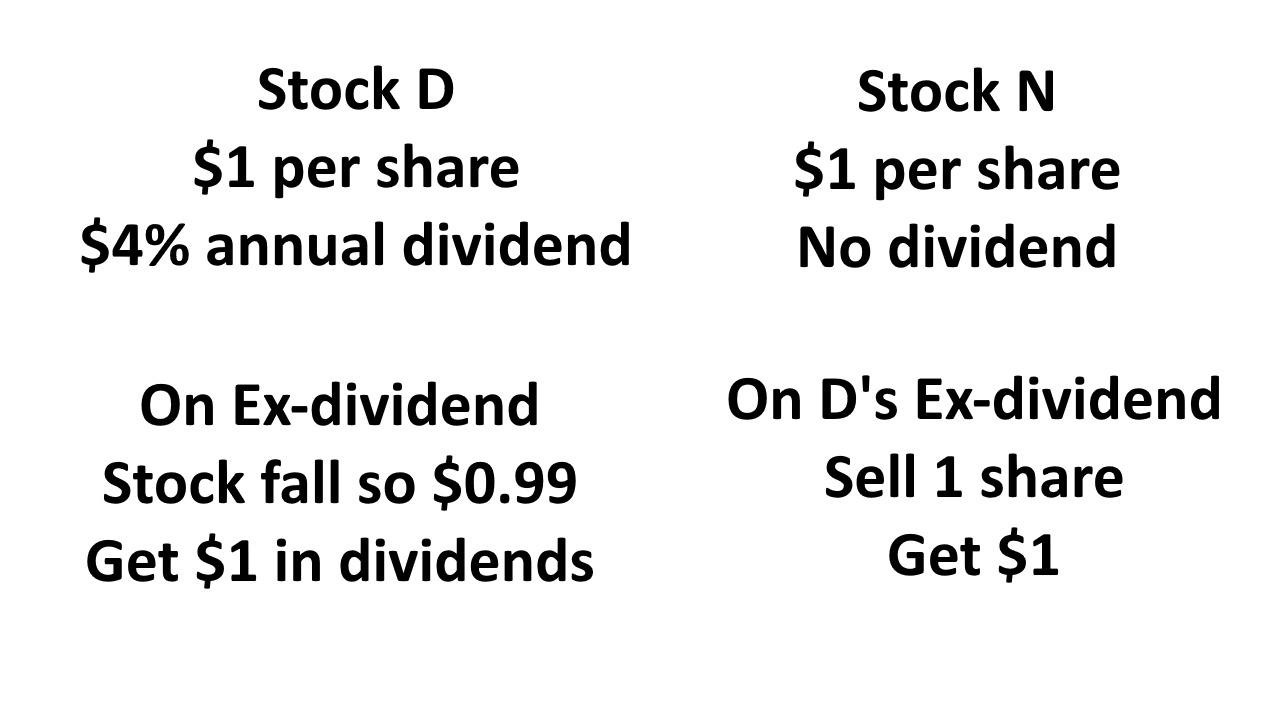

Consider again Stock D, this time priced at $1 per share and with a 4% annual dividend, and Stock N, this time priced at $1 and again with no dividend. If I buy 100 shares of each, selling 1% of my holdings in Stock N on Stock D’s ex-dividend date, on the first payout date, I will have 100 shares of Stock D, which is now priced at $0.99 per share, a $1 dividend payment, and 99 shares of Stock N, still priced at $1 per share. But I also have an extra dollar, as I sold one share of Stock N. The total value is $99 in Stock N, $99 in Stock D, and $2 income. Stock D and Stock N produced the same output despite being different types of stocks.

Understanding that any stock can produce the equivalent of dividends unlocks a world of stocks that are generally ignored when dividend-hunting. Dividend investors otherwise restrict themselves by limiting their stock selection to those paying dividends, which naturally leads to a less diversified portfolio. Naturally, once you realize every stock allows for the equivalent – indeed superior – dividends, you are no longer constrained to a limited basket of stocks.

The unbinding of restraints does not only end at stock selection. Dividend investors are constrained to quarterly payouts, set at predefined dates. The creation of your own dividends on non-dividend stocks – synthetic dividends – allows for flexible dividend payment dates.

Free from Dividends: The Benefits

Besides the obvious personal reasons, such as an immediate need for capital, the flexibility of dividend dates allows for a number of addition benefits. For instance, a dividend portfolio with quarterly payments is usually staggered, with income streams timed chaotically. But with synthetic dividends, an investor can ensure a stable quarterly or even monthly income – a much more reliable and manageable income stream.

Moreover, it is well-known that stocks have seasonality. This holds true for both sectors and individual stocks. With synthetic dividends, payouts can be timed with seasonality, liquidating shares to create dividends at seasonal highs and before seasonal pullbacks, leading to alpha over time.

Once an investor controls his own dividend payments, he will find himself free of a final risk that comes with dividend investing: dividend cuts. Even strong companies that have virtually zero risk of bankruptcy can spontaneously cut their dividends. For example, Disney was one such company; after years of dividend payments, investors found the company suddenly cutting its dividend to zero in 2020.

A dividend cut is an ever-present risk with considerable downside. Studies have shown that a dividend cut also leads to a decline in the stock price for roughly two weeks. Not only does a dividend cut delete the income-generating property from the stock but it also drags the stock downward.

But even if a dividend cut had no effect on the stock price, the cut itself hurts a dividend investor in a way that non-dividend investors cannot be hurt. In our Stock D/Stock N example, the Stock N equivalent of a dividend cut is losing shares. For example, if your 100 shares of Stock D are paying you a 4% annual yield and the company cuts the dividend to zero, the Stock N equivalent would be your 100 shares being reduced to 96 shares. Of course, with non-dividend stocks, this is an impossibility: Your shares cannot simply disappear. With a dividend stock, you are always exposed to the risk of your shares effectively disappearing.

In the end, dividends present more downside risk without any equivalent upside benefit once you incorporate the fact that dividend-equivalent income can be generated from non-dividend stock. Researchers taking a deeper look at this subject are still bewildered as to why dividends even exist under the current taxation system. Though looping back to the beginning of this discussion might give us an answer: The misconceptions regarding dividends could themselves be bolstering the continued existence of dividends, driving both investors and corporate management toward a suboptimal capital distribution strategy.

The actionable takeaway here is that income-seeking investors are better off creating their own tax-advantaged, time-flexible dividends from the entire world of stocks than being confined to the rigid subset of suboptimal dividend stocks.

No Comment